Service members have been asked to take on a great deal of international responsibility in the last year. Recently, a group of Democratic lawmakers released a video urging military personnel and intelligence officials to refuse unlawful orders, particularly those that might violate the Constitution. The message was straightforward but striking: even the lowest-ranking service members may ultimately be asked to serve as a final check on political decisions to use force.

At the same time, the Trump administration has pursued an increasingly assertive posture abroad. In early January, U.S. forces were sent into Venezuela to arrest President Nicolás Maduro. While polling on this specific action is limited, what we do have suggests broad public skepticism. According to a Quinnipiac poll conducted shortly after the operation, a majority of American voters opposed U.S. intervention in Venezuelan politics, and nearly three-quarters opposed sending U.S. ground troops to control the country. However, a CBS News Poll shows more ambivalence than support or dissension among Americans in general.

These events raise a deeper and more enduring question, one that extends beyond any single country or administration:

What kinds of military actions do Americans actually see as legitimate?

Polling often focuses on approval or disapproval of particular interventions. But legitimacy operates at a more basic level. It shapes whether new uses of force are accepted, questioned, or resisted before public debate ever reaches the details of a specific mission.

This is not the first time we have seen this pattern emerge. In earlier posts, we examined attitudes toward using the military to address domestic disorder and drug trafficking, comparing civilian young adults with ROTC cadets and military academy students. Those findings revealed a consistent theme: both groups were generally open to the idea of using troops in these contexts, but clearly hesitant to do so.

In neither case did we observe overwhelming enthusiasm for military involvement. Instead, support tended to cluster around conditional approval. This finding suggests a level of uncertainty rather than endorsement. Cadets and civilians alike appeared to recognize these missions as plausible, but also as departures from the military’s traditional role.

These earlier results help frame the current analysis. Together, they suggest that younger Americans do not reject military force outright, but they are cautious about extending it into roles that resemble policing, domestic control, or social problem–solving rather than national defense.

A Pattern Begins to Emerge

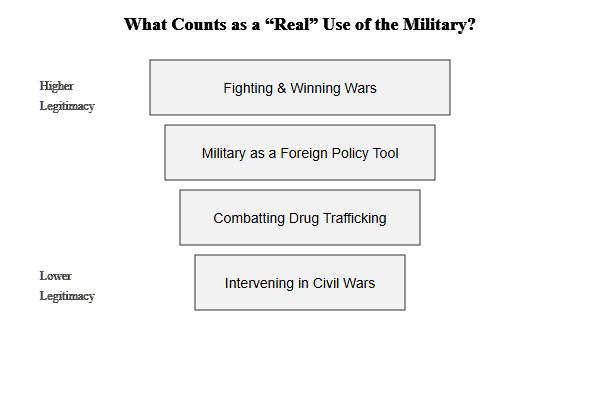

Across these four roles, a consistent pattern appears. Support for military action is strongest when the mission aligns with traditional war-fighting. As missions become more ambiguous, indirect, or political, support steadily declines.

Importantly, this skepticism is not limited to civilians. Even among ROTC cadets and military academy students—future officers who are deeply embedded in military culture—support becomes more cautious as missions move away from conventional combat. The next generation does not reject the military. But it does appear to distinguish sharply between defense and discretionary intervention. The graphic below captures this pattern conceptually.

What Comes Next

This post has focused on the big picture: how legitimacy frames public reactions to military force at a time of expanding executive authority and contested interventions.

In the next post (planned for February), we will walk through the data in detail, showing how support varies across civilian students, ROTC cadets, and military academy students. We will also see where those differences disappear entirely. Together, these posts aim to clarify not whether Americans support the military, but how they believe it should be used.